Citizenship Data & Data Protection: Evidence of Woolly Thinking?

This morning the Irish Times is quoting me in two pieces after the personal data of newly minted Irish Citizens was found to be published online in a searchable format.

This is a good example of the importance of an “outcomes focussed” approach to Privacy Impact Assessments and Data Protection in order to ensure risks are properly managed. It is a good example of the way in which a blind focus on statutory mechanisms to permit processing of data still needs to assess risks and ensure that the processing has a clear purpose that is both necessary and proportionate.

Is it searchable?

The Data Protection Commissioner previously ordered a website that was publishing a range of personal data about births, marriages, and deaths to make radical changes due to data protection concerns. The Government Departments that wanted to publish the data in a searchable format argued that it was data that was required to be part of a Public Register and all they were doing was making it available in a different format. The DPC prevailed, on the basis that the ability to search and scrape data from the website of living people represented a breach of Data Protection obligations. Changes to the data provided by that site had to be made to restrict access to data about living individuals. The data can still be obtained, but you have to go through the “traditional” step of going to a counter in a public office, filling out a form, and waiting for the data to be searched and provided, one record at a time.

That is a decent organisational and technical control to prevent unauthorised access.

The DPC has distinguished that case from the matter of new citizenship awards data being published on the basis that

Iris Oifigiúil cannot be searched by the individual name of the person naturalised and that this is an “important and significant” difference between this information and that which was published on the genealogy site.

My mind boggles at this frankly, given that the matter was brought to their attention because someone had googled their name and found the listing of all the names. “

They also seem to be taking the line that the fact that Iris Oifiguil was a “niche interest” publication (not widely read apparently) that this was a distingushing factor. That’s a dangerous precedent to set, which I’ll return to later.

Here are the facts:

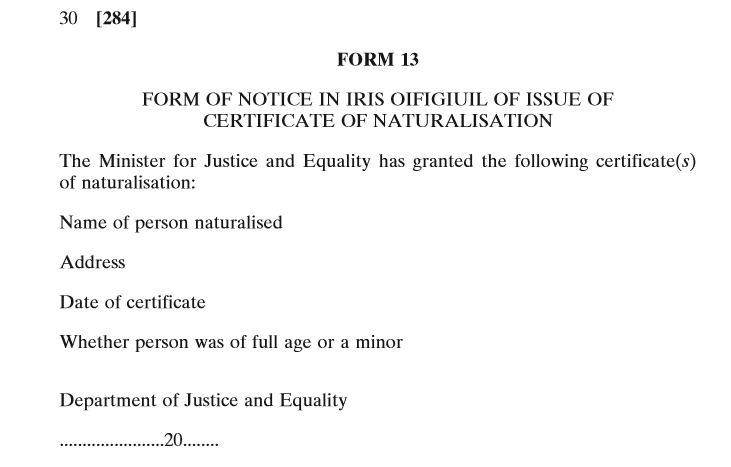

- Iris Oifiguil is published online as a pdf

- Google indexes PDF documents published online

- Data in it is searchable by Google

- The downloaded PDF can be searched by name.

I know at least one naturalised citizen. I was able to search Iris Oifiguil via Google to find data about that person. I was able to download the PDF file and search that for citizens by county or last name. That audit took all of ten minutes.

So: data about living individuals, which forms part of a Register, has been published online by a Government Agency in a format which allows it to be searched by name. This is exactly the same set of circumstances that arise in relation to the Genealogy.ie site. But the DPC on this occasion has decided there is no issue here.

Conclusion: Either the DPC rushed to comment in response to a media query (an error), or they didn’t understand the media question, or they don’t understand how searchable pdfs and search engine indexing works. Or they don’t want to rock the boat with the Public Sector (but it can’t be that because the ODPC is required by EU Treaty to be an independent body)

But isn’t the publication lawful?

The DPC has taken the position that the publication is required by law under the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956. Section 18(2) of the Act requires that there be a publication in “a prescribed manner” in Iris Ofiguil. Context: this 1956 Act was passed when Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the inventer of what we know now as the world wide web, was barely one year old. “Publication” in that context meant printing on a dead tree, not presentation in a searchable electronic form. Finding data required time and effort for research. Just like the researching of Births, Marriages, and Deaths that was so problematic in the case of Genealogy.ie.

The “prescribed manner” is set out in SI284/2011. That “prescribed form” simply states that there should be publication to Iris Ofiguil and sets out the data that will be published.

The legislation is, however, silent as to the purpose of publication or the necessity of publication. The Dept of Justice tells the Irish Times that there is a requirement for “transparency”, but this was met in 1956 with the requirement to publish in a a dead tree format. What is the purpose of publishing all the data in a searchable format online? Is it necessary to publish the data? Is it necessary to publish it online? Is that online publication proportionate to the “transparency” requirement that the Dept of Justice has referenced (but which does not have an explicit statutory basis)?

Furthermore, data processed must be adequate, relevant, and not excessive. One would have to ask how relevant and not excessive it is to publish the full names and home addresses of naturalised citizens. The requirement for “transparency” could be met more effectively through, for example, publishing the name and county of residence at date of naturalisation. This is particularly the case since the 2011 SI post-dates the enactment of the Lisbon Treaty, which made these rights fundamental rights for EU citizens and require legislation in EU member states to be consistent and compatible with those rights. An appropriate balance must be struck. That requirement was reaffirmed very strongly by the CJEU in Digital Rights Ireland v Ireland.

The DPC is relying on the existence of a requirement to publish that was created shortly after the inventor of the World Wide Web had himself been invented, and on an SI that sets out the data that the government has decided will be published but without any real clarity as to the purpose for the publication of ALL that data or the necessity of it being published on-line. They appear to be selectively avoiding the question of whether that processing is necessary and proportionate and whether the legislation that is being relied on is compatible with the Directive or the Article 8 Rights under the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

So, while there is a law that requires publication, it may well be that that law itself is unlawful.

What should/could the DPC do?

As an independent Regulator the DPC should be taking opportunities where a systemic issue arise from the unanticipated consequences of legislation to recommend that legislation be changed to address systemic gaps. They should not dismiss things on the basis that “nobody reads that thing”, which is essentially the position they seem to have adopted. My personal blog is not as widely read as the New York Times, but does that mean I should have carte blanche to publish personal data that I obtain under a law that predates the internet by 39 years (and barely post-dates the inventor of the world wide web)?

The DPC should encourage proper privacy impact assessments at the legislative stage to ensure that implementation of potentially laudable policies doesn’t wind up exposing personal data of individuals. While publication might be required by law, it is not required that that publication be indexed by Google.

The DPC could ask for the PDF edition of Iris Ofiguil to be blocked from Google search and other search engines and removed from their search indexes. After all, this is not something that is widely read (according to the DPC). This would, at least, address the symptom if not the underlying root cause.

The DPC could express concern that the Article 8 Rights of EU Citizens are not being respected with the level of granularity of data being published even in dead tree form.

That is what an independent Regulator would do.

What can naturalised Citizens do?

I would suggest, and have been quoted as suggesting, that naturalised citizens should contact Google and ask to have their data removed from its search indexes. It is their right under the current Data Protection Directive. Of course, Google may decline their request.

In which case the DPC will need to make a decision.

Will tweaking the Robots.txt file on Irisofiguil.ie fix this?

No. It won’t. In the same way as taking paracetemol to treat a headache doesn’t solve things if the headache is caused by a brain tumour.

Tweaking the Robots.txt file to stop the files being indexed by Google or other search engines will prevent the PDF files being indexed for search. Which will make it harder for people to find them. But won’t address the fact that data is still published in them that anyone with patience (or a bit of software) can eventually get access to by guessing URLs and file folder structures. Ironically, this is a problem the Data Protection Commissioner experienced themselves a few years ago when a blogger guessed the URL for their annual report and details were leaked before official publication.

The solution is to ensure that the data that is to ensure that any publication actually has a firm legal basis and that only the minimum necessary data is published. The pecking order, from most important to least, that must be respected is: Treaty obligations >> Directive >> Statute >> Statutory Instrument.

That means ceasing publication, doing a full Privacy Impact Assessment, and changing the law so that it is compatible with Treaty rights of Citizens.