The Politics of Data

Data is often political. But this post is actually about the processing of data by political candidates and for “electoral activities” in the Republic of Ireland. It’s topical because the Irish Data Protection Commission is in the early stages of an inquiry into the processing of personal data by a leading political party. The fallout from this is that the Oireachtas Housing Commitee (which oversees the electoral laws in Ireland) will be asking questions about how all parties use personal data.

I won’t comment specifically on the activities of any party or speculate on the details of the DPC’s inquiry. This blog post will instead summarise some of the key issues that need to be considered. I say summarise as this is a HUGE topic. I’ve delivered training on it in the past for clients (last time in Q4 2018 for the first election run in Europe post GDPR) and would be more than happy to do so again (we have a public course on this topic scheduled for late May).

Warning: This is a LONG READ.

The Data Canvas (and the Data-Driven Canvass)

In general, political parties live and die on data. But the last decade has seen a significant change in the nature of that data and the tools that are used to manage it, analyse it, and put it to use. This is a factor of the rise of social media and the ‘commodification’ of computing power and data analytics and processing technologies. This is not the election machine of yesteryear, but has become one in which those who have the best data, the most data, and the capacity to put it to the best use, win.

The Arsenal

In general, political parties in Ireland can have some or all of the following types of data:

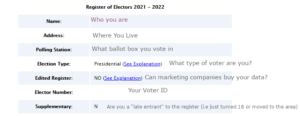

- Your entry in the Electoral Register (the full register).

- TDs, MEPs, and Councillors each get a copy of the draft Register of Electors under Regulation 6(1)(b to d) of Schedule 2 of the Electoral Act 1992. Regulation 6(2) also requires that a supply of forms for making claims to correct the register be provided – this is important when we come to considering purpose limitation later

- A copy of the full electoral register is also provided to election agents for nominated candidates for President, Dáil, Local Authority, or European Parliament elections under Regulation 14(4)(a) and (b) of Part II of that Schedule. Now… there is a key term in the legislation here that needs to be borne in mind… “duly nominated candidate”. This is important as the general derogations that apply to processing of data by sitting politicians or candidates for elected office are defined in terms of “electoral activities”, a term that isn’t actually defined anywhere. But… the “electoral activities” of a “duly nominated candidate” suggest a constraint on the processing activities that this data can be used for, and indeed a limit on the storage of that data.

- The marked electoral register

- Under Section 131 of the Electoral Act 1992 anybody can purchase a copy of the marked electoral register. The marked electoral register is a copy of the register that the polling clerk at your polling station uses to mark you off the list when giving you your ballot. It is the record that you have voted. The control on purchasing this is essentially little more than a promise not to do anything naughty with it in a statutory declaration.

- If this is obtained regularly (after each election or referendum), a very rich pattern of voting history can be developed for each voter.

- Details obtained from constituency contact or representations

- If you contact your elected representative they will usually keep a record of the issues that you have raised. This may be kept locally by your elected representative. But there are a range of products and services available now for “Constituent Relationship Management”, in the same way banks or phone companies keep your interactions “on file”.

- This can include your email address and telephone number if you give contact details.

- Details gathered from social media interaction, including visiting a Party website

- Political parties can gather information about you from your interactions on social media. This can be through directly asking you for information (“What’s your eircode?”) or through the use of analytics cookies and trackers that are used in ‘traditional’ online marketing, or through interactions on instant messenger apps.

- Bear in mind, if a political party has your name and your eircode (post code) and a general idea of your age they have two pieces of data needed to uniquely identify you back in the electoral register and can then associate your social media interaction.

- Information gathered from door-to-door canvassing or surveys

- A canvass on the doorstep is a great opportunity for a political party to tell you about their policies and promises. It’s also a great opportunity for them to find out about issues that matter to you as a voter and your likelihood of voting for that candidate or party. Sometimes this can be recorded for later analysis

- Surveys carried out on social media, through websites, or in person can also be a source of data about you, particularly if it is linked to data that could directly or indirectly identify you.

- Opinion polling data and focus group data

- Political parties regularly run opinion polling and focus group sessions as a way of getting the voice of the voter at a ‘macro’ level. If you want to know how the left handed gingers of Ireland feel about a thing (with a degree of reliability), get the pollsters in.

- Ballot box counts and Electoral tally data

- The tallying and counting of votes in an election count provides candidates and parties with data about how each polling station voted in an election.

This is not an exhaustive list and the potential data and data sources are a factor of budget, awareness, and know-how.

The Impact

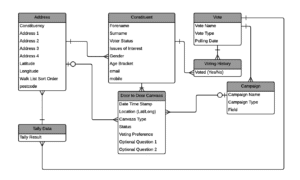

Once you go beyond the basics of the electoral register and information that a local representative captures from interacting with their constituents, the volume and variety of data is constrained largely by budget, technical capability, and focus. But even with the basic information from the Electoral Register, the Marked Register, the record of interactions on social media or in the constituency office, and tally data, a very rich picture can be developed of the individual voter:

- Who they are? Where they are? What they care about? Whether they vote? How often they vote? What their issues and interests are? Whether their interests are consistent with or at odds with the voting patterns of their ward? Other ‘soft intelligence’ about them as a person?

My colleague Katherine and I actually looked at this for a client nearly a decade ago and our book on Ethical Data Management includes a mockup data model based on that project that shows how different data can be connected and linked to provide a rich view of a voter.

There is also nothing necessarily wrong with any of this, as long as it is done in compliance with data protection laws. However, because of the very rich tapestry of the individual that can be developed from basic data sets when combined, it is essential that candidates for office, holders of office, and political parties pay careful attention to what those laws actually say and require them to do to balance the scale with regard to the rights and freedoms of the constituent.

The GDPR Perspective

The GDPR sets out the fundamental legal framework for processing data about people. The GDPR applies to all organisations that process personal data. “Electoral activities” and “political parties” are mentioned only once in the Regulation, in Recital 56. That recital clarifies that where the operation of the democratic system in a Member state requires that parties compile personal data on political opinions of individual, that can be permitted in the public interest “provided that appropriate safeguards are established”.

There is no broad exemption for politicians or political parties under GDPR. Therefore, the fundamental principles and obligations of GDPR that apply to any other Data Controller apply to political parties. A full exploration of the fundamental principles of data protection as they apply to political parties and candidates is beyond the scope of this post (I do a full course on this for clients). Things I won’t cover in this blog post include the question of who is the Data Controller for this data once it is held by a candidate or by a political party, and the thorny questions of Joint Controllership that arise based on CJEU case law, and the implications of how that is governed for overall compliance (that’s a blog post for another day). Neither will I look at the issues of cross-border transfers outside the EU/EEA (but that’s a significant one).

Nor will I spend any time on the question of ePrivacy compliance by political parties. By this I mean the use of cookies on websites, use of email addresses, SMS, or instant messengers to push out messages to constituents. The rules here are extremely clear and are quite often ignored because of a misplaced belief that there is an exemption for politicians. There isn’t. Which brings me to the last thing I won’t cover – training of politicians, candidates, constituency staff, and volunteers on their data protection obligations and what the law actually is as opposed to what they might want or believe it to be. I won’t be talking about that. But it’s something that is needed as an organisational control under Article 24 GDPR. I also won’t be talking about the need for political parties (and, depending how you answer the question about Data Controllership above, possibly individual candidates or elected reps) to maintain a Register of Processing Activities under Article 30 GDPR, nor will I waste time on the need for political parties to appoint DPOs under Article 37 GDPR. I also won’t be talking about the case law of the CJEU that makes organisations Joint Controllers with social media platforms or other platforms that they might use if there is any shared or common purpose, and the Data Controller/Data Processor issues that

Neither will I consume electrons on the need for political parties conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments when introducing new systems or processes under Article 35 GDPR. And finally, I’m going to skip over the thorny question of volunteers working within a party structure who have access to personal data of members or constituents and the fact that they are technically Data Processors and, as such, require an agreement in writing that covers off the requirements of Article 28 GDPR. And don’t get me started on the complexities of non-party / non ‘Official’ canvassing groups self organising on social media during a campaign. That just wrecked my head back in the Presidential campaign trying to identify and mitigate the risks there. And I also won’t touch the processing of special category data by parties as not-for-profit organisations as some of that is caught by Article 9 GDPR, but context can be a bitch in practice.

That’s quite a lot of things I won’t be looking at in a blog post that’s already much longer than my usual. Seriously.. the list of things I won’t be talking about is longer than one of my usual blog posts here. (If you want to know more, we’ll be running our previously in-house course on Data Protection for Political Parties and Activists as a public course in a few weeks time).

However, there are some aspects which deserve some specific attention. As starting point, the bedrock of data protection is the principle that data should be processed fairly, lawfully, and transparently. And the personal data processed by a Controller should be necessary and proportionate to the purpose for which the data was originally obtained. These principles are fundamental. So fundamental that they are enshrined in Article 8 of the Charter of the Fundamental Rights of the European Union and in Article 16 of the Treaty for the Functioning of the EU.

Fair and Lawful Processing

One common mistake that people make when talking about data protection issues is to assume you need consent for everything you might do. You don’t. However, you must have an appropriate legal basis. One such legal basis is a statutory basis, where the processing is in the public interest and the basis is set out in EU or Member State law. Of course, it isn’t enough to just have a ‘bit of ould law’ to provide a fig leaf for your processing. The law must be necessary and proportionate and there must be appropriate safeguards in place to protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of data subjects. Also, there must be a specific purpose that is being served by the processing. Finally, when we are looking at legislation and interpreting it, it’s important to remember that domestic legislation must be interpreted in a manner that is compatible with EU law and if no interpretation is possible that is compatible with EU law, any offending provision needs to be set aside in its entirety.

The Electoral Register

In terms of access to the electoral register, there is a clear legal basis under the Electoral Act 1992 for the processing of this data. However (and this is a key point), the legislation envisages that that data is given to a “duly nominated candidate” or their agent (for the Electoral Register) or to an incumbent elected representative (for the Draft Electoral Register). It does NOT explicitly allow for that data to be provided to a corporate entity such as a Party for that to be combined with other data, although that might be permitted if the Party is providing data processing services to the Candidate for the candidate’s purposes and on the candidate’s instructions and the data is not being used for other purposes.

In this context we need to consider the purpose that sits behind these provisions of the Electoral Acts.

For the provision of the Draft Register under Schedule 2 of the Act, the fact that that also requires the provision of forms to allow errors in the register to be corrected would suggest that the purpose of that processing and the public interest being served in that context is to ensure the accuracy of the Electoral Register and to allow errors or omissions to be corrected so that no potential voter is disenfranchised. With regard to the provision of the full Electoral Register under Regulation 14 of Schedule 2 of the Act, it is clear from the wording that the legislature intended that the full Electoral Register would be provided only to nominated candidates for election. Which would suggest that the purpose for processing envisaged in 1992 is to enable that candidate to get elected in their constituency. The public interest being served is to allow candidates to canvass their electorate and ‘get the vote out’. However, that brings with it a purpose limitation question…

When the election is over what is the legal basis for the ongoing processing of the electoral register outside of that election? There are very few grounds, if any, under Article 6 GDPR that apply, so we will park that until we look at the Data Protection Act 2018 and what it says about what can be done with data by politicians.

The Marked Register

The marked register can be bought from the Clerk of the Dáil or from a local authority (depending on whether the election was a local election or not). This is allowed under Section 131 of the Electoral Act. This creates a legal basis for the supply of “copies of or extracts from” a suite of documents set out in Section 129(2) of the Act. The safeguard here is that you have to pay a fee to cover the cost of copying and promise not to do anything naughty with the data, and actual ballot data is excluded under Section 130. Also what you get are photocopies or scanned copies of the physical documents, not an electronic report.

As to whether the transcription of the marked register into a database so that a political party can analyse which voters actually vote constitutes lawful processing, we need to examine the intended purpose of the access being provided. Firstly, Section 131 of the Act is entitled “Inspection of Certain Other Documents“. This would suggest that the purpose intended by the legislature for any processing of this data is for the purposes of inspecting the register to identify any cases of questionable voting (it is very important to identify cases where people may have voted from beyond the grave). As the legislature in 1992 probably couldn’t foresee the advent of data-driven campaigning it’s reasonable to suggest that they didn’t consider the possibility of the marked register being transcribed into database, linking a voter’s entry on the Electoral Register, and being retained to provide a snapshot of that voter’s voting patterns in different types of ballot.

Indeed, when we look back at the text of section 129(3) of the Act, we see that a hard retention period is defined in legislation for this data. It should only be retained for six months by the Clerk of the Dáil and then it must be destroyed unless a High Court Order prevents this or unless the Clerk of the Dáil has reason to believe the documentation may be required for a prosecution of an offence or the purpose of a petition to the Courts.

So, what is the Public Interest basis for people being able to get the Marked Register that the 1992 Act serves? To act as a safety net on the electoral process, but within a six month period. To allow inspection of the documentation relating to the governance of the ballot (not the ballot itself) and to allow the prosecution of offences under the Act and to allow people to litigate the outcome of an election if necessary.

The development of a database of voters that tells you if they vote, and what they vote on, and lets you identify whether they are in an area that votes your way was probably not the purpose the legislature intended for this data. And if it was, we would need to see additional safeguards defined in law in respect of this data. As such, I have significant doubts that the processing of the marked register data for any purpose other than inspecting the voting record in a particular election to identify potential issues with the conduct of the election is compatible with obligations under GDPR to process data on a lawful basis. But the DPC will inevitably make a determination on this and other points.

Transparent Processing

Another key element of the fundamental principles is that data must be processed transparently. Under GDPR this is essentially addressed under Article 5(1) and specifically under Articles 13 and 14 of the Regulation. The counterweight is the Right of Access under Article 15 which entitles a data subject to a copy of the data that is held about them by the Data Controller. That has to be provided in an intelligible form without undue delay or within one month. Access Requests are another thing I won’t get into detail on in this post.

Article 13 requires that any data controller who is processing personal data about a data subject to provide them with certain information BEFORE they obtain and process that data. Failure to do this is an offence. The most common way this is done is through a Data Protection Notice on a website or information that would be provided to a data subject orally or on a handout. So, if someone working for a political party or a politician asks for information such as your address or eircode when you are interacting with them on Facebook or social media, they should be able to tell you what they are going to use it for, how long they will keep it, and a list of things that are defined in Article 13. If they don’t (or can’t) then there is a problem.

Article 14 is often overlooked but, in this context it is probably more important than Article 13. This is because Article 14 applies to data about people that a Controller gets from a third party, i.e. not from the Data Subject themselves but by being sent it by someone else. In the context of a political party, third parties would include Local Authorities or the Clerk of the Dáil, and would also include any volunteers who ‘donate’ data, list brokers who the party might purchase data from, or social media platforms that provide tracking or analytics data that can be linked to an identifiable individual.

Overall, Article 14 of GDPR replicates Article 13 in terms of the information that must be provided. But Article 14(3) and Article 14(4) of GDPR brings a small kicker that dials up the transparency requirement further. These provisions require that data subjects are notified by Controllers that they have this data “within a reasonable period” and no later than one month after getting it. Also if the data is to be used for a purpose other than that for which it was originally processed that needs to be communicated also, along with the relevant information about legal basis etc. for this new processing purpose.

If this isn’t done, then the processing is not transparent or lawful under GDPR, notwithstanding there may be a lawful basis for the processing. This was borne out in a 2015 CJEU case involving public sector data sharing called the Bara case (see summary here from McGarr Solicitors). That case re-emphasised the importance of the transparency principle in the processing of personal data, even in the public interest on a statutory basis.

The Data Protection Act 2018

“But the Data Protection Act 2018 has huge carve outs for politicians!” I hear you cry. Well, yes and no I respond. Certainly there was an attempt to make a landgrab for unfettered powers to do pretty much anything with personal data for political ends when the Data Protection Act 2018 was being drafted. Thankfully, cooler heads prevailed (and Cambridge Analytica happened which spooked people). The main provisions under the Data Protection Act 2018 are Section 39, Section 40, and Section 48.

Section 39 – Communication with Voters

Section 39 creates a public interest basis in statute for communication by parties with data subjects in the course of electoral activities. This means that one of the specified purposes a political party, candidate, or office holder may pursue with data they have obtained fairly and lawfully is to communicate in the course of electoral activities. There are a few key points to unpack here.

- This does not create a carte blanche for willy nilly gathering of data. It allows that there is a stated purpose of communicating and, effectively, acts as a statement that it’s considered in the public interest that people can be communicated with by their politicians. In writing.

- This is without prejudice to the lex specialis of the ePrivacy Directives that relate to the use of electronic mail and SMS and other electronic modes of communication, which require consent. So… if a politician wants to add you to their email list or send you campaign correspondence by SMS or Instant Messenger, they need consent for that, but a letter is covered by section 39.

- “Electoral Activities” is not defined as a term here or anyway. It’s a bit like pornography.. we’ll know an electoral activity when we see one. So it needs to be interpreted. And it needs to be interpreted in a way that upholds the public interest objective but is in line with the EU law requirement that data be processed for specific lawful purposes subject to appropriate safeguards. A conservative interpretation might look to the Electoral Act and its trigger for providing the Electoral register – which is that someone requesting it is a “duly nominated candidate” for some election.

This is something that needs to be clarified, not least because Article 23(2) of GDPR requires clarity in any national legislative measure restricting rights or obligations under GDPR.

Section 40 – Processing of Personal Data and Special Category Data by Elected Representatives

This has public interest basis written all over it in HUGE letters. It’s a specific basis for processing data about constituents who the elected representative or their staff are helping with things. The “business of staying elected” so to speak. But again, this is not an absolute carte blanche. It requires the party or elected rep to put in place appropriate controls over the security of the data.

This also only provides a lawful basis for processing requests or representations from data subjects or other persons acting on their behalf or for the elected representative to go and request data from other parties on behalf of the data subject.

Section 48 – Processing of Personal Data revealing political opinions for electoral activities and functions of the Referendum Commission.

This is basically a basis for opinion polling and recording information that might be gleaned on a canvass or from interaction with voters. It still requires the data to be obtained and processed fairly and transparently. And all the other provisions of GDPR still apply. And “suitable and specific measures” need to be applied to safeguard the fundamental rights of data subjects. They are found in Section 36 of the Act. Regulations can be made setting out other safeguards, but a safeguard on the safeguards is that the DPC needs to be consulted (which suggests a data protection impact assessment would need to be done).

It all comes back to Fair, Lawful, and Transparent (and the core obligations under GDPR)

Ultimately, the lawfulness or otherwise of any processing of personal data by a political party or a candidate for elected office really comes down to the attention paid to the fairness and transparency of processing. Even where there is a lawful basis, if there is not transparency then the processing does not comply with obligations under GDPR.

When we consider the lawful basis for processing, we also have to ensure that that is assessed through the lens of EU law and the jurisprudence that has developed in respect of data protection law over the last thirty years. Thirty years ago social media was a science fiction pipe dream. Thirty years ago the tools and technologies for data analysis and data linkage we have today were beyond the reach of most organisations. Thirty years ago all politics was local, and the legislation reflects the mindset and technical capabilities of the time.

Careful consideration of the purposes for processing and how the obligations that exist under data protection law today can be applied in the context of data governed primarily by legislation that is thirty years old is essential for any political party, candidate, or elected representative. It is not enough to assert you are compliant. Article 5(2) of GDPR requires that you can show how you are compliant.

And of course, the Latin maxim “ubi saxa coniecit et videat si speculum in manufactis habitat” applies to all of this from a political perspective.

How can Castlebridge help?

The Castlebridge team have worked with political parties, election campaigns, and referendum campaigns to help address their data strategy and data protection compliance challenges.

We can help with compliance gap analysis, DPIAs on new systems or processes, staff training, or outsource DPO services to help mitigate potential conflicts of interest in a Party structure. Get in touch to find out how we can help.

We have a public course on Data Protection for Political Parties and Candidates coming up next month. Details will be posted shortly on our Events page. Previous clients will get a discount on the course fee.